On Friday, the last day of trading for the December NYMEX Henry Hub contract, trading was light, but the news was heavy. The newest COVID-19 variant B.1.1.529, named by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the Omicron variant, was first reported to WHO from South Africa on November 24. By the time energy markets opened Friday morning after the Thanksgiving holiday, the Omicron fear had moved into the markets.

US travel stocks (airlines, cruise lines, hotels, booking websites) all took a large hit on Friday, with front-month contracts for crude oil and gasoline selling off about 10% and 12% respectively, or $10 per barrel of crude and 28¢ per gallon of gasoline. Other refined fuels like Ultra-Low Sulfur Diesel (NY Harbor ULSD) also sold off in a similar ratio to gasoline.

Natural gas, however, wasn’t so bearish. Instead of selling off 10% or more, the December Henry Hub NYMEX contract closed up $0.38 that day, an increase of almost 10%. The final settlement for the December contract was $5.447, down just slightly from November’s final settlement of $6.202, and October’s final settlement of $5.841. This makes the trailing 3-month average settlement price of natural gas the highest 3-month average since March 2009.

Some might point to the thinly traded December contract (only 6,257 trades for the December contract versus 148,000 trades for the January contract) as the contributing factor to its volatility, but all of Q1 2022 rallied as well. This leads one to believe that it wasn’t just traders rolling out of their December positions that fueled the rally. In fact, by the last day of trading for a prompt month, the following month (prompt+1) has typically been the highest traded month for at least a few days.

The knee-jerk rally in natural gas prices last Friday could be due to an inverse reaction to the movement in crude prices, which is the same reason natural gas prices rallied during the spring of 2020. During the spring of 2020, when COVID-19 was causing massive demand destruction of oil and distillates, crude prices tumbled, while natural gas prices rallied. The fundamental reason behind this divergence in trends is due to the massive amounts of associated natural gas coming from major crude reserves, like the Permian Basin in West Texas.

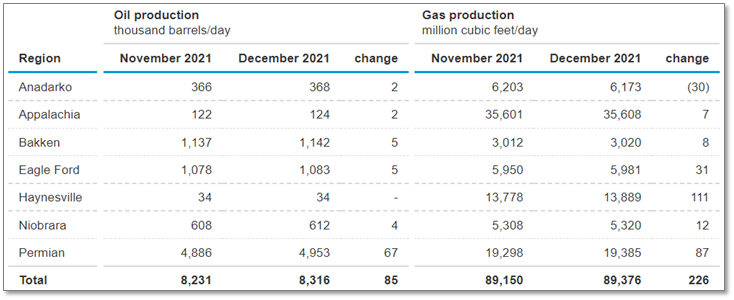

The Permian Basin is the largest crude oil-producing region in the US and the second-largest natural gas-producing region. A massive drop in crude prices usually slows capital spending and production of crude, therefore reducing natural gas output. Figure 1 shows how domestic crude oil and natural gas production have varied over the last two months.

Figure 1: Domestic Crude Oil and Natural Gas Production from eia.gov

Coincidentally, as the markets began trading on Monday morning, the fears of Friday began to fade. Crude recovered by $1.80 per barrel and natural gas sold off by $0.62 per MMBtu by market settlement. At this same time last year, the 90-day standard deviation for daily market movement was about 13¢. By the end of this month, that daily standard deviation has doubled to 26¢.

It may be tough to predict anything these days, but one sure bet is that volatility has returned to the natural gas market.